Druckerfreundliche Version/ printer-friendly version

Druckerfreundliche Version/ printer-friendly version

Shandong Drum Songs of the Bible[1]

圣教小说山东鼓词

Contents

Eight Drum Songs of the Old Testament

The Shandong Opera “The Great Flood”

Roman Martyrs’ Stories

Children’s Stories

Translators are Matchmakers

Illustrations

Bibliography A and B

Chinese abstract

Schoolbooks of the Shandong Mission

In 2007 Professor Malek wrote a stimulating article on the educational material published by the S.V.D. Shandong mission, followed by a detailed biographical list. [2] It was this article by Father Malek that inspired me to collect more information on the subject. The Shandong teaching material Father Malek describes in the article covers many subjects: Chinese grammar, Western geography, Latin and Greek, mathematics, philosophy, psychology and even some popular stories with a literary flavour. Attached was a photo of the title page of such a booklet with the intriguing title: “Fei Jinbiao’s Drum Songs to the Old Testament (1918)”.[3] This title especially awakened my interest. With the help of the staff of the “Monumenta Serica”, the original and many other similar little booklets were found, and I was allowed to use them for this article.[4] Father Malek generously granted me access to his personal library and let me use an unpublished article on this subject. There must have been many such popular little stories, yet they are now scattered in various places. I myself have seen 15 of them. They fall into 3 groups:

Drum Song Stories from the Old Testament

Stories about Roman Martyrs

Children’s Books.

Most booklets were published at the beginning of the 20th century between 1915 and 1920 and were printed by the Yanzhou Catholic press of the S. V. D., famous for its wide range of Catholic and scholarly publications.[5]

The stories were helpful for Chinese and for Western readers, since they had a double function: First, they served as schoolbooks for Chinese children, in elementary as well as in middle schools. Following the abolition of the Chinese civil service exams in 1905 there was a great demand for modern, i.e. Western education, world history, modern science, Western eography and Western culture und literature. Much educational material of the Shandong mission was written for the German-Chinese school in Taikia (Daijia 戴家) and the college in Tsining (Ji’ning济宁). Secondly, being written in easy colloquial Chinese, they provided lively teaching material for missionaries who needed to learn the difficult Chinese language. The stories are not only instructive but also very entertaining. The authors use traditional Chinese storytelling modes, like Shandong Drum Songs and Chinese Opera.

In this article I have used a comparative approach, contrasting the Chinese stories with their European sources and showing how Chinese authors and Western priests of the Shandong mission successfully combined elements of their two traditions, found points of contact between Chinese and Western culture and created interesting and original stories.

Eight Drum Songs of the Old Testament[6]

Father Joseph Hesser (1867-1920), director of the Catechist’s School of S. V. D. in Yanzhou, had already translated the stories of the Old and New Testament into Chinese prose in the early 1900’s.[7] A decade later they were transformed into “Shandong Drum Songs” (Shandong dagu 山东大鼓), a traditional form of story-telling with a history of many centuries, which was and still is very popular in Shandong.[8] There are various styles of performance. Usually the storyteller will accompany himself on a drum, but there can also be other instruments and female singers as well. Popular themes are hero stories like The Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi三国演义) or Water Margin (Shuihuzhuan水浒传), love stories like Dream of the Red Chamber (Hongloumeng红楼梦) or West Chamber (Xixiangji西厢记), criminal stories like Judge Bao (Baogong an 包公安) and humourous Clown stories and satires (huaji fengci滑稽讽刺). The Drum Songs were performed in temples or the market place, the audience being mostly farmers and poor people. But they were also popular among the educated, who admired their literary charm and vigour.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Yanzhou Press published a cycle of eight stories from the Old Testament. The author was Fei Jinbiao 费金标, a traditional scholar (xiucai 秀才) and famous storyteller of the times:

1. Chuangshi ji创世纪 (Genesis)

2. Chugu ji出谷纪 (Exodus),Huji ji户籍 纪 (Numbers),Shenming pian申命篇(Deuteronomy)

3. Yuesuwei zhuan约苏位 传 (Joshua),Zhanglao zhuan长老传 (Judges),Hude zhuan卢德传 (Ruth)

4. Qianliewang zhuan前列王传(First book of Kings)

5. Zhongliewang zhuan中列王传 (Second book of Kings)

6. Houliewang zhuan后列王传 (Third book of Kings)

7. Danier zhuan大尼尔传 (Daniel),Ruobo zhuan 若伯传(Job), Rudide zhuan 儒第德传 (Judith), Duobiya zhuan多俾亚传 (Tobit) Yuena zhuan约纳传 (Jonah)

8. Aiside zhuan爱斯德传 (Esther), 爱斯忒拉 传 Aisituila zhuan (Ezra) Naheimi zhuan 纳黑弥传(Nehemiah) Majiabo zhuan玛加伯传 (Maccabees) [9]

The stories are translated into colloquial Chinese and adapted to Shandong Drum Songs, with a narrator alternately speaking in prose and singing in rhyme. As is usual in traditional Chinese storytelling, the performer will appeal to his audience in a familiar way, asking listeners for their opinions and comments on the action. Important details will be repeated several times, so that a noisy and fluctuating audience on a market place will be able to catch up with whatever they have missed. The narrator will always inform his listeners about sudden turns in the story, i.e. if he leaves aside one thread of his tale and takes up a new one. At exciting moments he is sure to pause and ask his audience “to wait for the next scene”, thus increasing the suspense, while he himself can take a rest and collect some money:

The moon rises in the west on the river/ Let us tell again a story of old times

Dear audience … guess who is that person?

Telling a story, I have not two mouths. I must leave this, and tell the other.

Let’s have a rest and smoke a pipe.

Let me now string the Pipa and continue the music.

If you want to know how this meeting went, you have to wait for the music in the next scene. [10]

Regularly, jokes and funny scenes are added to enliven the biblical stories. For instance, the prophet Elisha’s servant Gehazi appears as a comic figure, creating chaos and making the audience laugh (no. 6, p. 34f.)

Often details are added, connecting the old Bible stories with present Shandong life, i.e. a song about a terrible famine:

(song): In a year of great famine the troops had encircled the capital/ Food in the town was a hundred times more expensive/ One donkey’s head was worth 80 diao/ Dove’s droppings cost 5 diao/ The people could really not keep their existence/ People would devour people to keep alive/ [11]

There are many allusions to traditional Chinese culture: For instance the palace of Babylon looks very similar to the court of the Chinese emperor, with palace ladies singing “Ten thousand Years” (wansui 万岁) three times and kowtowing in honour of the emperor. (no. 6, p. 96). The audience is told that some biblical events “happened at the time of our Zhou dynasty” (no. 6, p.101). There are also many popular proverbs and quotations from the classics.

While in the Old Testament Israel is punished for worshipping Baal and other wicked gods, in the Chinese text these deities look like devils from Buddhist hells or like monsters in the fantastic archaic geography Shanhaijing 山海经 (The Classic of Mountains and Seas):

(Song): Some adore Yaksha devils/With red beard, green eyes and red lips/ Others worship evil monsters/They believe those with black faces and red hair to be gods/ Worship those with pig’s snout and vampire’s teeth/ Or with legs of wild beasts and bird’s body/ With human head and fish body/ With bull’s face and horse face horrible/ Countless all those statues of wicked gods.[12]

When Moses is born, the Bible characterizes him as “a fine child” (Exodus, 2). Fei Jinbiao, on the other hand, adorns his baby features with the physiognomy of the Chinese future hero: “Square face, big ears. More intelligent than others, has all the talent for great deeds”[13] As a boy Moses gets a model Chinese education: “First classic poetry and history, then essays; having only once skimmed through a text, he already could recite it”.[14]

In his “Third Book of Kings” Fei Jinbiao, himself a scholar who passed the exams of the Qing Dynasty, even added a letter in classical Chinese (wenyan文言) with learned allusions, in order to appeal to the more educated members of his audience. While the Bible says only:

“At that time Marduk-Baldan son of Baladan king of Babylon sent Hezekiah letters and a gift, because he had heard of Hezekiah’s illness”. (2 Kings, 20 „Envoys from Babylon“)

Fei Jinbiao writes:

I, Baladan, King of Babylon, have many times visited His Majesty Hezekiah, king of Juda. I have heard that your might shakens the world, and your virtue moves the whole earth. The Barbarians pledge their allegiance. The Golden Crow (the sun) obeys you. The shadow of the sun has gone back ten degrees, thus every day is five hours longer. This is unheard of since thousand antiquities! Your imperial body has suffered from heavy illness, but is now happily healthy and can do without medicine. This gives royal me boundless consolation. I send my congratulations and a small present. I pray that you kindly accept this. With respect I send this. [15]

It is quite impossible to translate the classic beauty of style and learned allusions into plain English, the letter should really be translated into Latin.

In order to adapt the Bible text to Chinese customs, Fei Jinbiao sometimes feels free to change the content of the stories a bit. For instance, the story of “Ruth” describes how Ruth, having lost her husband while still very young, decides to stay with her mother-in-law, which is in accordance with the Confucian ethical code. On the other hand Ruth, on the advice of her mother-in-law, finds herself a second husband, which is certainly not the way that a chaste Chinese widow should behave. Fei Jinbiao first quotes a popular Chinese proverb criticizing this act:

A good horse does not carry two saddles/

How can this good woman marry two men?[16]

Then the narrator explains, that Ruth values most the Confucian virtues of “chastity and filial piety” (jiexiao节孝), that she married not for lust but in order to give birth to a son, whose offspring will be the famous king David. The scene in which Ruth lies down at night at the feet of her future husband on the threshing floor, is discreetly left out.

Fei Jinbiao is fond of making jokes and sometimes engages in mock learned discussions: According to him there are, compared to the Bible, many wrong traditions about the beginning of the world: In China the first men were created from mud as in the Bible, but the historians forgot to mention the names of Adam and Eve, a big mistake. In Chinese history there is also a Great Flood, but the waters were regulated by the Chinese emperor, the “Great Yu” (da yu大禹), thus Noah and his family of eight on the Ark were not mentioned, another big mistake. But, so Fei Jinbiao argues, the Chinese at least preserved the character chuan 船 ( “ship”). He first criticizes the scholars of the Ming Dynasty for their incorrect analysis of this character and then gives his “correct” interpretation: chuan 船 “ship”, when split into its three parts “boat”, “eight”, “mouth” is proof that in antiquity the Chinese already knew about Noah and the Great Flood – long before Christian missionaries told them about it:

船 chuan ship

舟zhou boat - 八ba eight - 口kou mouth or person

“Noah on his Ark with his family of eight” (No. 1, p. 20)

The Shandong Opera The Great Flood

Hongshui mieshi juben. 洪水灭世剧本. The Great Flood. Opera. Written by Fei Jinbiao. Yanzhou 1921.

Fei Jinbiao made the story of Noah into a veritable Chinese opera. The work must have been very well received, since it soon went into a second edition. As the Yanzhou Press announced:

The author is Fei Jinbiao. He adapted “The Great Flood” of the Old Testament to the style of a Chinese opera, describing feelings and scenes which captivate the heart of the reader.[17]

Fei Jinbiao certainly can captivate the hearts of his audience – his opera is full of suspense. The basic facts are the same as in Genesis 6-9: Noah was a good man, and so were his three sons and family. But since the people of the world were wicked, God decided to destroy them all except Noah. God told Noah to build the Ark, thus saving him, his family and all the animals.

In the Chinese version, every scene starts in the traditional opera style with a short poem foreshadowing and summing up the main content. The actors first introduce themselves, alternately singing in rhyme and speaking in prose. First Noah appears, informing the audience about all his ancestors, longing for the peaceful old times of Adam and lamenting about the present wickedness of the world. After Noah has left the stage, the “Angel” appears:

I am the Angel telling you that God will reward the good and punish the wicked. God has made Heaven and Earth for the use of men. He commands men to cultivate virtue and do good deeds, so that after their death they can go to Heaven and enjoy happiness as rightful sons of God… God has ordered me (an俺) to appear to Noah in a dream and save him and his family of eight…God will destroy everything with a Great Flood. That is such a pity![18]

In Chinese folklore, we find an abundance of gods, fairies, ghosts, devils, animal and flower spirits – but no angel. For a Chinese rural audience of that time the Christian God and his angels were something new and had to be explained in more detail. The Chinese Angel speaks to his audience in a relaxed familiar way, using Shandong dialect, i.e. saying an (俺 “I”) instead of wo (我). The Angel – like the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy Guanyin Pusa 观音菩 萨 – is full of pity for the people of the world who are going to perish in the Great Flood. When the Angel tells his audience that God commands men “to cultivate virtue and do good deeds” (xiude ligong 修德立功), this not only sounds Christian but also has a Buddhist flavour. Before leaving, the Angel sings in poetic verse: “Having told you this, I will now fly up to Heaven”. And then in colloquial prose: “Noah, Noah, do not believe that this dream will not come true!”[19]

Realistic details make the story more lively and closer to Shandong life: For instance, there is a scene in which Noah’s son Shem tries to hire a carpenter to build the Ark, and haggles about the money:

Carpenter sings: If you want me make an arc, the price is one hundred sixty, if less, I won’t do it!

Shem sings: I will give you exactly 100 copper coins/ In bad weather and rain the same.

Another man comes in admonishing them: The government price is one hundred and twenty/ You two should be fair and don’t quarrel!

Shem sings: Well, well, well, you come with me/ Let us select some wood in the mountains.[20]

There is much fun and comedy, when Noah tries in vain to admonish the wicked people of the world. While good Noah sings in majestic rhymes, the unrepenting people make fun of him in colloquial prose, with disrespectful jokes and plays on words:

People speak: This old guy really becomes more peculiar the older he gets. Who can ever drown the world?

Noah sings: Last night I had a dream

People speak: I knew that it was a dream!

Noah sings: This dream was really nightmarish

People speak: True, you certainly had a nightmare!

Noah sings: A Great Flood (hongshui) will cover the whole earth

People speak: Don’t bother about green floods or red floods (hongshui), the more water we get the better![21]

The last passage is a pun, hongshui meaning “Great Flood” (洪水) as well as “red flood” (红水)

There follows a bloodcurdling attempted murder scene, recalling the famous Shandong robbers of the Water Margin: A man persecutes threatens another with a knife, claiming that this scoundrel rapes virtuous girls and women. When Noah tries to admonish the knife bearer, this man gets furious and turns against Noah himself, singing: “You try this knife – see whether it’s sharp or not/ I’ll raise my weapon and crack your head!”[22] Happily, the Angel appears and covers the world in darkness so that the murderer can see nothing and Noah escapes at the very last moment.

After Noah and his family have entered the Ark and no rain comes for seven days, the Angel reassures the audience: (Angel sings):

Our Lord is just sitting on the colourful rainbow/ Making calculations that the day for the Great Flood has come/ [23]

The Great Flood is described with vivid images, showing how the water, step by step, rises from the ground up to the sky:

(Angel sings): …Just see how the people on the ground are all drowned/ Those who climbed trees are now rolling like dragons in the waves/ Those who climbed the summits could first save their life/ But later the flood killed all of them/ This rain fell forty days/ Forty days and forty nights, incessantly/ Not only the ground flooded/ Even the high mountains were all covered/ Ants wanting to go into their holes found them full of water/ Winged birds could reach no sky … [24]

When the water finally recedes and the bird comes back to the Ark with a green branch, Noah is full of joy, which breaks out in spontaneous exclamations of happiness: “Hooray! Lord, oh my Lord, I really must praise you!”[25]

The Chinese opera “The Great Flood” adapted the biblical text to the level of Shandong farmers, most of whom could probably not read or write. But since their childhood they had often listened breathlessly to the traditional stories of Old China, which the storytellers would recite to drum music in front of the temples and in the market places. Here the Chinese “translator” – or perhaps we should say “author” – Fei Jinbiao has combined this tradition with the Bible text, writing in a lively and colourful style, full of fun and laughter, tragedy and compassion.

Yet we should also admire the Western priests of the Shandong mission for their tolerance. Fei Jinbiao was taking great liberties with the Holy Bible, adding elements that could be criticized as irreverent, too Chinese, too funny or even unchristian.[26] Yet the Catholic priests of the Shandong mission saw no problem here. Both Father Roeser (in 1916) and Father Henninghaus (in 1921), leading priests of the Shandong mission, gave their permission, written in Latin, to print “The Great Flood”:

Nihil obstat. Yenchowfu, die 17. m. Januarii 1916. P. Roeser. Reimprimatur, Yenchowfu, die 2. Sept. 1921. + A. Henninghaus.

As Father Malek has pointed out, the theatre was considered to be dangerous for Christians and was therefore not used for evangelisation for a long time, except in Shandong:

All the more it is interesting that the Divine Word Missionaries used it at the beginning of the 20th century as medium in their work. They broke new ground with this initiative, at least in China and at the local level. [27]

As it worked out, the little stories were a very successful Chinese-Western cooperation, creating rather enjoyable reading.

We might well ask why Fei Jinbiao added the “Angel” and gave him such a leading role in his opera. No angel appears in the Bible text, and there are no angels in Chinese folklore. I suggest that Fei Jinbiao did this for artistic reasons: The Christian God was high and almighty and not easy to impersonate on the stage. Instead, the Angel, who is much more human and close to the audience, takes His part. Besides, the Angel is sometimes very good fun, because he is charmingly naive, for instance, when he tells the audience, that God is sitting on his rainbow doing his calculations. Fei Jinbiao with his classical education was certainly not naive himself, but his Angel is. However that may be, the Angel is certainly an interesting addition to the Chinese opera “The Great Flood”.

Roman Martyrs’ Stories

The Shandong mission published quite a few stories about Christian martyrs, among them even a Latin-Chinese edition Acta Sanctorum Martyrum.[28] Many stories were adapted from Jesuit sources. For Shandong missionaries at the beginning of the 20th century, the old theme was again of topical interest, because of their own suffering during the Boxer Rebellion.

Zhiming xiaozhuan guci 致命小传鼓词 (Drum Songs about Martyrs). 2 volumes, Yanzhou 1915.

On the little booklet there is no name of a writer or translator. Luckily, an advertisement by the Yanzhou Press helped me to find the names of both the author of the English source of the story and the Chinese translator:

This is a famous novel of Cardinal Wiseman. It was translated and adapted to Drum Song by Mr. Fei Jinbiao, in two volumes. The price is 15 cents. [29]

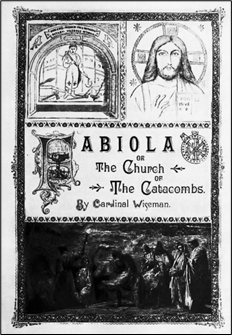

Nicholas Wiseman (1802-1865) was an Irishman, who was educated in Rome, became archbishop of Westminster and Cardinal in Rome. In his leisure time he wrote a historical romance, Fabiola: A Tale of the Church of the Catacombs. (1854), which became immensely popular. It was translated into many European languages, made into two films and has just been reprinted.[30] It was this novel which was made into a Shandong Drum Song by Fei Jinbiao.

Fabiola is set in ancient Rome before and after the victory of Constantine. Some characters of the book are based on biographies of Christian Saints such as St. Agnes, St. Sebastian, and St. Pancratius, while others, like the main character Fabiola, are fictitious. Fabiola is a beautiful but spoilt young lady from an aristocratic Roman family, who later reforms and becomes a Christian.

In his version, Fei Jinbiao has left out a great number of historical chapters, in which Wiseman describes the antique Roman theatres and baths, the development of the “Church of the Catacombs”, gives graphic plans of the underground graves etc. Fei Jinbiao also ignores the many learned Latin and Greek references to the “Acts of Martyrs” (Acta Sanctorum Martyrum) and other historical material.

But all of the highlights are kept, following one another in much more rapid succession than in the original: The Chinese audience is introduced to daring heroes, wily fortune hunters, devilish poisoners, arrogant young ladies and saintly Christian slave girls. Religious devotion and sacrifice contrast with the perennial greed for sex and money. Like a film camera, the story moves quickly between different places, different people and different threads of action: The narrator tells us about the splendours of Rome, takes us into the labyrinth of the catacombs, shows how the martyrs were tortured and sent to fight with wild animals, describing saints and villains, and showing us visions of Heaven and Hell.

Fei Jinbiao often builds bridges between China and the West. Just like the Jesuits many years before him, he sets the Christian God and Confucius side by side, as in this poem:

The great Christian God is the principle of Truth/ Confucius declared, if he heard in the morning about the True Way, he would gladly die in the evening/ Being suddenly enlightened about the Right Way/ And not wavering till death, that is a True Man.[31]

On the other hand, the typical Chinese ideal of the “filial son” [32] is dramatized in quite a different way from the original. In Fabiola two Christian boys are in prison awaiting execution. Parents and friends implore them to save their lives by apostasy, and they seem to waver. The Christian officer, the holy Sebastian, rushes into their prison “like an angel of light”, rebuking them sternly with the Bible words: “He that loveth father or mother more than Me, is not worthy of Me”. The two boys “hung their heads and wept in humble confession of their weakness” and quickly resolve not to renounce their faith.[33]

Fei Jinbiao describes a much more heartrending scene:

(The father Tang Guillin speaks to Sebastian): … “Save the life of my sons! See the tears of their mother and my earnest exhortations. I have exerted all my strength, till my sons finally wanted to reform. But with your intimidation and deception you send them again to death! You let them forsake father and mother and become unfilial sons! (buxiaozhizi不孝之子)! What kind of sense does this make? Besides, all others urge them to live, you alone want them to die! This is not only unreasonable, it is a crime against all human feelings!” (dafan renqing大反人情)….[34]

Even the Christian general, the saintly Sebastian, agrees, that it is the duty of every filial son to be obedient to his parents. Only much later does he add that an even better way to serve one’s parents would be to persuade them to become Christians and enjoy eternal happiness together. In the Chinese version the conflict is not between black and white, right and wrong – there is understanding for both sides.

The story of the great villain Fulvius/Fu Feisi, a spy and unscrupulous fortune hunter who has sent many Christians to their death, is also treated differently than in the original. After the victory of Constantine, he has lost everything and desperately breaks into the house of young, rich and beautiful Miss Fa (Fabiola) extorting money from her and threatening her with death: … “this is my day of Nemesis. Now die!” (Wiseman, Fabiola, p. 426)

Fei Jinbiao’s villain, like the wild Shandong robbers of Liangshan Moor, not only wants to kill but also to rape Miss Fa:

(Fu Feisi sings) “To heaven I have no way/ To earth I have no door/ You even want to drive me away quickly/ Where should I go for shelter ….

(prose) “Do not tell me to go away, even you will not be able to go.” Saying this, he threw Miss Fa on the bed …[35]

At the end of the story, after twenty years, a “stranger from the east” appears who turns out to be none other than the villain Fu Feisi/ Fulvius. In Fabiola this is not so very surprising, since the Christian reader is often reminded that the Shepherd will bring back the lost sheep and that a loving God can pardon all sinners. In the Chinese version this comes as a real surprise. Fei Jinbiao keeps the reader in suspense about the identity of the “stranger from the east” to the very last, thus making the story much more dramatic.

Sure of his talents as an artist, Fei Jinbiao often takes liberties with his text and looks down on pedantic realism. An example is the description of Maximian (Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus, ca. 240 – 310), the barbarian West King of Rome. In Fabiola he is characterised thus:

Gigantic in frame … with eyes restlessly rolling in a compound expression of suspicion, profligacy, and ferocity, this almost last of Rome’s tyrants struck terror into the heart of any beholder, except a Christian. Is it wonderful that he hated the race and its name?[36]

This is certainly frightening, yet without transgressing the bounds of reality. Not so Fei Jinbiao who indulges freely in fantasy, scoffing at all would-be critics:

(sings) This West King had a depraved heart/ And looked horrible/ People would be frightened to death/ He was actually a giant measuring one zhang and twenty/ (about three metres twenty)

(speaks) Dear audience, you will ask me, was he really so huge? I tell you, I am talking about Chinese „chi“, in the West they are „mida“ (metre) – to make absolutely sure, you should really check yourselves. But don’t be so pedantic and listen again:

His shoulders were broad three inches and three tenth

There you go again and say, “three inches” are enough, why add “three tenth”? Let me tell you, there are fat ones and skinny ones, the fat ones are three inches three tenth. As a narrator and singer I do not care for such narrow-minded pettiness….

His pig’s snout and vampire’s teeth were not like those of men/ His steely protruding eyes spit fire …[37]

Cardinal Wiseman wanted to write the history of the first Christians, of the “Church of the Catacombs”. Therefore in Fabiola the historical element plays a central role. In Fei Jinbiao’s version, history gives way to artistic aims, i.e. to entertain by a thrilling story.

Kumin darong. 苦民大荣 (From Misery to Glory). By Luo Siduo 罗司铎 (Father Luo), Yanzhou 1916.

As author only the name “Luo Siduo罗司铎” (Father Luo) was given, which is the Chinese name of Father Roeser, S. V. D. By luck I found a slip of paper in German stuck on the cover of the booklet indicating that the author was R. D. A. de Waal.[38] This helped me to find the German source of the story, Valeria oder der Triumphzug aus den Katakomben (Valeria or the Triumphal Procession out of the Catacombs), by Anton de Waal.

Monsignor Anton de Waal (1837 – 1917) was a German priest and church historian, who spent most of his life in Rome. He carried out archaeological excavations in the catacombs and established the Collegio Teutonico del Campo Santo in the Vatican. His novel treats the same theme as Cardinal Wiseman’s Fabiola, again using the Roman persecutions of Christians followed by the conquest of Rome and the victory of Emperor Constantine in the year 337 as the historical background. The story centres on a noble Roman family: The father, Rufinus, is Lord Mayor of Rome and believes in the old Roman gods. Both the mother, Sophronia, and the daughter Valeria are secretly Christians. At the beginning of the story Sophronia, in order to avoid being raped by the depraved Roman emperor Maxentius (Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius, 278 – 312), takes her own life. Later her husband and their daughter Valeria are sent to prison and threatened with a cruel death, but are saved in the end by emperor Constantine. Like Fabiola the story includes many learned historical annotations about ancient Rome and the catacombs. Yet the style of the narration is very different, i.e. rather full of an exalted Christian fervour and pathos. Nowadays the story cannot be read for literary enjoyment, but rather as a historical document giving information about the spirit of the times.

Although the Chinese version names only Father Roeser as translator, he certainly had a Chinese native speaker at his side whose name we do not know. At the beginning there is a reproduction of a dark and gruesome picture showing Christians burying their martyrs in Rome’s catacombs. As in the Chinese Fabiola, all learned references and descriptions of ancient Rome are left out. The style is more moderate, lacking the Christian pathos of the original.

There are some variations in view of the different cultural backgrounds of the readers. One example is the controversial theme of suicide. In our story the Christian lady Sophronia kills herself, in order not to be raped. This was praiseworthy in Rome as the case of Lucretia shows, yet for Christians it was a mortal sin. In his foreword to the third edition of 1896 de Waal mentions that he got many complaints about this “unchristian” suicide and therefore made some modifications – for example, adding a note quoting St. Augustine De Civitate Dei who generally condemned suicide but made some exceptions.[39]

For most Chinese readers suicide under such circumstances was praiseworthy. As was the case in ancient Rome there are also many stories about suicides of chaste Chinese women. Thus, Sophronia writes a letter to her husband justifying her deed as God’s will: If she was raped, she would be ashamed to look her husband in the face or to look into God’s holy face. In her heart she has heard a voice: It is God’s will that you free yourself from this villain. At this point the Christian narrator comments: Since Sophronia was unaware that the Christian religion forbade suicide, she did not commit a sin. (p. 9f.) Though this may sound a bit like sophistry, yet the translators found a way not to condemn the Roman lady to hell.

Sometimes different Chinese and Western images and values are successfully blended. An interesting example is a strange miraculous scene in the Mamertine dungeon, when Valeria baptizes her father and in a religious rapture (Verzückung) suddenly sees her mother Sophronia in heaven:

Soon, Valeria “with divine eye” (shenmu 神目) saw men and women in paradise, among them her mother, who asked her and her father to come to Heaven. But in between was a deep abyss with an enormous dragon who opened his mouth wide to devour them. Valeria spoke “like in a dream” (rutong mengli 如同梦里), her father could hear her, when she said suddenly: “Dada, don’t be afraid. If you stamp your foot on the dragon’s head and trust Jesus’ holy name, he will not hurt you. Let us pass quickly, my mother is waiting for us. The misery is temporary, happiness will be eternal.[40]

In Europe expressions like “spiritual eye” (in German “geistiges Auge”) mean seeing things beyond reality. On the other hand, the Chinese shenmu 神目 (divine eye) alludes to the magic “third eye” (disanzhi yanjing第三只眼睛) on the forehead of the god Erlang (Erlangshen二郎神), which enabled him to see invisible things. Even though the Chinese and Western images evoke different associations, the visionary experiences are very much alike. Talking in a trance, crossing an abyss or stamping on a dangerous dragon’s head are also dreamlike experiences not difficult to understand either for Europeans or for Chinese.

Children’s Stories

Western missionaries in China founded many schools, for primary as well as for higher education. In Shandong, a most active organizer was the Steyler Bishop Anzer (1851-1903), who with the help of the Chinese and German governments, opened the first Chinese-German school in 1902 in Jining.[41] His successor, Bishop Augustin Henninghaus (1862-1939), asked Father Georg Maria Stenz (1869-1928) to become director, first of the school in Taikia 戴家(1904-1909) and afterwards of the Chinese – German College in Jining (1909-1927).[42] Stenz was a lively and successful writer, who published widely about his life in China and about Chinese culture.[43]

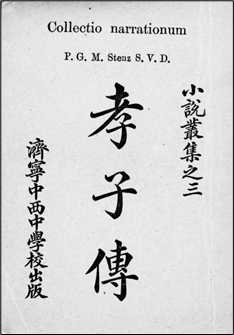

Xiaozizhuan孝子传 (The Filial Son). Collectio narrationum P. G. M. Stenz S. V. D. Published by Ji’ning Western – Chinese Middle School, Yanzhou 1920.

The story is about a young Indian prince, who – despite the strong resistance of his father – finally succeeds in being baptized and becoming a Christian. Since his father is a devout Brahmanin, the son faces the typically Chinese dilemma of filial piety vs. Christian faith: Should he be obedient to his father and follow Brahmanism? Or should he rebel and follow the Christian God? The Catholic priest advises the son to be patient and tolerant, using his “divine eye” (shenmu神目) and praying constantly. Thus, the Christian baptism of the prince first takes place only spiritually, i.e. in a dream. When the son is imprisoned by his angry father, the narrator asks the readers:

Dear believers, think about it. Is it possible that God will desert such a devout filial son? One evening, God showed himself before Xidi’ang (the son) in a dream. In his dream he saw the priest Ao, who stood smiling before his bed, holding a crucifix and saying to him: Xidi’ang, you can now follow Jesus and carry the cross of the world. God loves you and fulfills your prayer. Come, I will baptize you, so that later you can go to heaven and enjoy eternal happiness. Xidi’ang was so overjoyed that he could not speak … Only when he awoke, he realized that it was a dream.[44]

The end is similar to a famous scene in the Shuihuzhuan水浒传. The father is captured by robbers and about to be hanged on a tree, but just as the rope is already around his father‘s neck, the filial son hurries to his side, heroically sacrificing himself in order to save his father’s life. The son goes to Heaven, moving the father so deeply that he converts to the Christian faith as well.

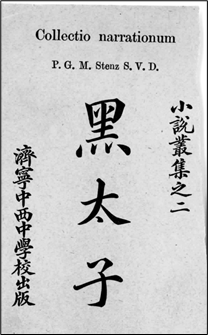

Heitaizi黑太子 (The Black Prince). Collectio narrationum P. G. M. Stenz S. V. D. Published by Ji’ning Western – Chinese Middle School, Yanzhou 1920.

The Black Prince also takes place in India and treats a similar theme. Again the story centres round the father-son relationship. Since the prince becomes very attached to a Catholic priest, his Brahamin father allows him to go to a Christian school, but he must swear never to be baptized. The school life described in the story seems to be an idealized picture of life in the Chinese-German School in Shandong, where Father Stenz was director. Again, dramatic elements from the traditional Chinese adventure story are introduced. This time the help comes, surprisingly realistically, from the British army. When the Catholic priest is captured and tortured, the British army marches in like a deus ex machina. The priest, instead of becoming a martyr, is saved from his tormentors. He generously forgives them and when even the English Queen sends a reprieve, the criminals are spared the death penalty.

This is a rather interesting mixture of fiction and truth. In reality, such incidents with missionaries were often unscrupulously used by the foreign powers to extort huge compensations from China. [45]

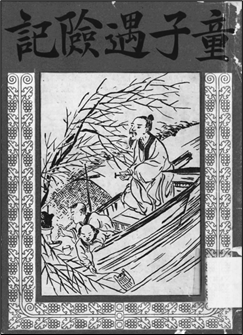

Isilan tongzi yuxianji 伊斯蘭童子遇险记 (Iceland Boys meeting Danger). Yanzhou 1931.

The Yanzhou Catholic printing house published quite a few children’s stories, which were very much in demand, since there were practically no such books in traditional China at that time. At a very early age the children would start to memorize classical texts like Tang poems and the Confucian classics in order to pass exams and become officials later. There were of course interesting novels like Xiyouji 西游记 (Journey to the West) or Sanguo yanyi 三国演义 (Three Kingdoms), but for these a fairly good command of Chinese characters was needed. And as for the many stories about love and adventure – they were thought unsuitable for children and therefore generally forbidden.

On the cover of Iceland Boys no author is named. Yet there is a preface by Liu Baohua 刘保华, who introduces himself as translator. Liu tells his little readers about the strange and beautiful country called Iceland, and especially emphasises the fact that he has translated this tale not into classical Chinese (wenyan 文言), but into colloquial language (baihua白话):

This story has been written in colloquial language, in a vulgar and unadorned style, very easy to understand. When you read it you will not be able to stop, the intelligent will be instructed and the stupid will be enlightened. It will open heart and eyes, it is really a treasure for all times and a world rarity.[46]

He also mentions that the author is Siwensong 斯文松(Svensson). I found out that Jón Svensson (Jón Stefán Sveinsson, 1857-1944) was a Jesuit priest from Iceland and a famous writer of children’s stories. His boy hero’s name “Nonni” is the familiar form of Svensson’s first name Jón. In his books Svensson writes about his childhood in Iceland, his life in a fishing village and his adventures on the ocean and in the mountains. His stories were written in German, translated into several languages and made into films and TV serials.[47] After some searching I discovered the original German stories, which Liu Bohua had translated into Chinese.

The Chinese version has two parts. In the first, “Nonni and Manni”, Nonni tells about his life as a fisherboy, about a “magic flute” which was supposed to attract fish and about an adventurous boating trip with his little brother Manni. When in mortal danger, the two boys take a vow, promising that if God saved them, they would later become missionaries. They are saved by a French ship and escorted home to their happy parents.

In the second part, Nonni, his friend Elis, and a dozen other schoolmates set out in a boat to enjoy “the ocean on fire”, i.e. a spectacular marine phosphorescence. When he is accidentally hit on the head by an iron anchor, Nonni falls into the sea. Praying to God, he is saved by an Irish ship, together with all his friends.

The Chinese version is a quite faithful translation of two German stories [48]. Yet there are some alterations. Foreign languages and customs receive particular emphasis. While Nonni and Manni are rowing on the ocean, they come into contact with foreign warships and commercial ships from France and England. First the little boys just shout the only French word they know: “Napolun拿破仑“!(Napoleon). Later they learn the French words “non” and “bonsoir”, to be pronounced through the nose. When they come to an English boat, they even manage a real dialogue with the foreign sailors: “Good evening”, “Who are you?”, “We are Icelandic boys” etc. This is done with the help of an older boy who translates from “Islandic” – i.e. Chinese – to English and back to Chinese. The little readers are even informed that Irish is different from English and are given an onomatopoetic imitation of Irish sounds:

The (Irish) captain smiled to me, placed his hand on my head and “diliandulu” talked a while. Even though we could not understand it, yet reckoned he talked well, since we heard him repeat many times “Poor little boy”. (p. 135)[49]

In a short epilogue we are told that the early vow of the two boys to become missionaries was not fulfilled later. The younger brother Manni died early, the older studied a long time and forgot about it:

Since he (Nonni) has not even achieved the grade of a priest and is now already middle-aged, it would be a bit late to set out to foreign parts and preach to the people there. (p. 153)[50]

This is a bit of self-irony, since Svensson actually became a priest, though not a missionary. In this little story praying to God is important, but missionary work is no longer the only theme. Just as important is imparting knowledge about foreign countries and about their languages, i.e. English and French.

Translators are Matchmakers

We have seen that the Chinese and Western translators of our little stories worked for a better understanding between China and Europe in many ways. Thus, the Shandong Fathers, in Father Malek’s words, “continued the accomodation tradition of the Jesuits”[51]. Instead of one-sidedly forcing the Chinese into European ways, they tried in their translations to understand and adapt themselves to Chinese culture.

In China, such mediation by translation has a history of nearly two thousand years. Qian Zhongshu 钱锺书 (1910-1998) produced illuminating research in this field. In his article “The Translations of Linshu”, Qian comes to the conclusion that one important job of the translator is the art of “matchmaking”.

In ancient China – just as in ancient Greece – foreigners were looked down upon as wild beasts or birds. Their – for the Chinese incomprehensible – language was called “bird-talk” or “croaking”. Quoting from the Han Dynasty Lexikon Shuowen jiezi 说文解字 (Explaining and Analyzing Characters, early 2nd century), Qian starts from an explanation of the etymology of the Chinese character for “translation”:

… e囮, means “to translate”. The bird-catcher enchains a living bird to tempt others. … (Qian comments): Since the Southern Tang Dynasty etymologists explained “translate” as translating into the language of barbarians, birds and wild beasts – just like a bird-catcher lures birds.[52]

Thus a basic job of the translator is to attract and to seduce. He has to keep an eye on his public and play the part of the matchmaker between the two cultures. In the same vein, many centuries later we find Goethe’s famous saying: “Übersetzer sind als geschäftige Kuppler anzusehen …” (“Translators are to be seen as busy matchmakers.”)[53]

When in the third century Buddhist monks came to China and translated the Buddhist scriptures, they developed new and more sophisticated theories of translation. Three different schools were founded, which exist to this day: The school of faithful translation (zhiyi直译), the school of elegance(yayi雅译) and the school of popular translation (suyi俗译).

The monk Dao An 道安 (314-385) was among the first to advocate the “faithful translation”. He wanted to translate the holy scriptures into Chinese without changes. Yet he soon found that this was impossible. In his treatise “Five Treasons” (wu shiben五失本) he wrote: If one follows faithfully the Sanskrit, the Chinese sentences would be upside down, this is the first treason. Then, there would be cultural differences:

The Buddhist scriptures are deep and simple. But we Chinese love a beautiful style. If we want to convert the Chinese … this is impossible without Chinese rhetoric. This is the second treason.[54]

The Jesuit missionaries, the Shandong Fathers, and most translators all over the world have come to the same conclusion: A verbatim translation would very quickly scare away all believers and readers.

Next, the famous Indian monk Kumarajiva (Jiumoluoshi鸠摩罗什, 344-413) propagated and practised a different strategy. Kumarajiva cultivated an elegant style, which won him many believers among the educated Chinese. Stylistically bad translations he criticized passionately without mincing words:

When translations from Sanskrit, even though the sense is correct, are lacking in literary beauty, this is like offering your guests already chewed food; it is not only tasteless, it also makes you vomit.[55]

Kumarajiva used a method, which more or less is followed in China to this day: He first recited a sutra in Sanskrit. Then translators translated it orally into Chinese. Afterwards the different versions were discussed by hundreds of monks and corrected. Only then was the translation written down.

Apparently the Shandong priests adapted a similar method, naturally with some variations. The little stories are written in simple, but fluent Chinese, certainly not by German priests, but by Chinese native speakers. On the flyleaf, before the name of German priests like Father Stenz or others, one often finds the term shuyi 述译, i.e. “oral translator”. Thus we can surmise that the German priests would translate a text from German into Chinese orally, while at the same time their Chinese partners would write it down in fluent, idiomatic Chinese. This written version was afterwards discussed and corrected by the German Fathers. A confirmation of this can be found in a foreword by Fei Jinbiao, in which he thanks Father Roeser for helping him with the sometimes problematic translation of names of cities or persons in the Old Testament.[56]

The third school is that of “popular translation”. After Kumarajiva, the monks addressed themselves not to the educated, but mainly to the common people in the market place. Usually, the Buddhist priest would first recite the scripture in classic Chinese. Then followed popular explanations, often accompanied by music, pictures, songs, comic scenes, theatre plays – the famous, all-beloved storytelling and story singing (shuoshu说书,shuochang 说唱). We have seen that the Shandong priests, and especially the talented storyteller Fei Jinbiao, used this tradition with great success.

Admittedly this art of matchmaking was not always the guiding principle. Even in our little stories quite a few prejudices and limitations can be detected. For instance, in schoolbook stories like The Filial Son or The Black Prince, Christian priests, Chinese converts and Christian schools are very much idealized, while believers of other religions are usually in the wrong and often come to a bad end.

In some rare cases there is even a total lack of esteem for the other culture: In Fabiola as well as in the Chinese adaption there is a scene in which a cultured Roman, after becoming a convert, smashes all the beautiful statues of Greek and Roman gods in his park. This is done, I am sorry to say, on the good advice of his Christian priest, and as a reward for this barbarian behaviour the Roman gentleman is promptly cured of his gout.[57]

Another debatable point is the passionate glorification of martyrdom. Dying a martyr’s death is described as something very desirable for Christians, being the key to paradise. It is like “going to a great feast”, and one victim even goes so far as to kiss the instruments of torture. Nowadays hearing about such heroic deeds, we would be more likely to associate them with fanatic Islamic terrorists than with so-called “civilized Christians”. Yet such views were rather typical for the times. Many young European missionaries, setting out for China at the beginning of the twentieth century, were eager to fight as “soldiers of Jesus” and to become martyrs.[58] On the other hand, there is even now a strange attraction in reading these little stories about the cruel fate of the early Christians. What could be the reason for this sympathy? For one thing, reading a martyr’s story is something very different from really dying as a martyr. It is rather like seeing a Greek tragedy. It helps to see our own life in a new perspective, and this can be a great solace.

However that may be, we certainly can see that the longing for martyrdom did not turn the Christian authors into inhuman fanatics. On the whole, the Chinese little stories are free from too much moralising or heavy missionary bias. The authors not only preached, they also wanted to entertain and to inform about foreign customs and languages. We can see that Chinese and Western authors respected each other and were trying to draw East and West together.

This worked especially well in the stories of Fei Jinbiao, a creative writer who transformed the old Bible and martyr stories into lively Shandong Drum songs, with scenes full of fantasy, shocking suspense and humorous relief. And it is just as admirable that the Steyler priests had the courage to print these texts without fear that somebody might accuse them of lacking respect for the Holy Bible and the memory of Christian martyrs.

It is certainly a pity that we know so little about the Chinese translators who did such an important job. Even about so brilliant a writer as Fei Jinbiao we have very little information.

We can be truly grateful to Father Malek, since he has done most of the work of collecting the booklets, doing research on them and saving them from oblivion.

Bibliography A:

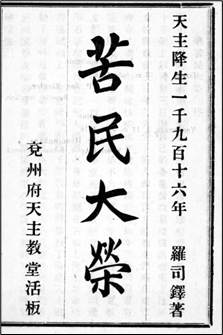

Shengjiao gushi xiaoshuo guci圣教古史小说鼓词, Drum Song Stories from the Old Testament. Shandong Shouzhang Fei Jinbiao zhu山东寿张费金标著, written by Fei Jinbiao from Shouzhang in Shandong. Yanzhou tianzhutang yinshuju huoban兖州天主堂印书局活版, published by the Catholic Yanzhou Press with movable types. 8 booklets. Tianzhu jiangsheng yiqian jiubai shiba nian 天主降生一千九百十八年, in the year A. D. 1918.

1. Chuangshi ji创世纪 (Genesis) Yanzhou 1918, 79 pp.

2. Chugu ji出谷纪 (Exodus),Huji ji户籍纪 (Numbers),Shenming pian申命篇(Deuteronomy), 68 pp.

3. Yuesuwei zhuan约苏位传 (Joshua),Zhanglao zhuan长老传 (Judges),Hude zhuan卢德传 (Ruth), 54 pp.

4. Qianliewang zhuan前列王传(First book of Kings), 138 pp.

5. Zhongliewang zhuan中列王传 (Second book of Kings), 126 pp.

6. Houliewang zhuan后列王传 (Third book of Kings), 121 pp.

7. Danier zhuan大尼尔传 (Daniel),Ruobo zhuan 若伯传(Job), Rudide zhuan 儒第德传 (Judith), Duobiya zhuan多俾亚传 (Tobit) Yuena zhuan约纳传 (Jonah), 134 pp.

8. Aiside zhuan爱斯德传 (Esther), 爱斯忒拉传 Aisituila zhuan (Ezra), Naheimi zhuan 纳黑弥传(Nehemiah), Majiabo zhuan玛加伯传 (Maccabees), 119 pp.

The Shandong Opera The Great Flood

Hongshui mieshi juben. 洪水灭世剧本. Chinese Opera: The Great Flood. Shandong Shouzhang Fei Jinbiao zhu山东寿张费金标著. Written by Fei Jinbiao from Shouzhang in Shandong. Yanzhou tianzhutang yinshuju huoban兖州天主堂印书局活版, published by the Catholic Yanzhou Press with movable types. Tianzhu jiangsheng yiqian jiubai ershiyi nian 天主降生一千九百二十一年, 第二次出版,Second edition in the year A. D. 1921. (First edition 1919), 67 pp.

Stories about Roman martyrs

Zhiming xiaozhuan guci 致命小传鼓词 (Drum Songs about Martyrs). Shandong Nanjie zhujiao Han Zhun山东南界主教韩, by bishop Han Zhun from Nanjie in Shandong, 2 vols., Yanzhou 1915. Translator Fei Jinbiao费金标. Adapted from Fabiola. Or the Church of the Catacombs (1880) by Cardinal Nicholas Patrick Wiseman.

Kumin darong. 苦民大荣(From Misery to Glory). By Luosiduo 罗司铎 (Father Roeser). Adapted from Valeria oder der Triumphzug aus den Katakomben (1884) by Monsignor Anton de Waal, Yanzhou 1916.

Children’s Books

Xiaozizhuan孝子传 The Filial Son. Collectio narrationum P. G. M. Stenz S. V. D. Author : P. Geyser S. Y. Oral translator (yishuzhe译述者):Father Stenz S. V. D. Ji’ning zhongxi zhongxue chuban济宁中西中学校出版. Published by Ji’ning Western – Chinese Middle School, Yanzhou 1920.

Heitaizi黑太子 The Black Prince. Collectio narrationum P.G.M. Stenz S.V.D. Author: P.A.v B. S. Y. Oral translator: Hantschau. Published by Ji’ning Western – Chinese Middle School, Yanzhou 1920.

Isilan tongzi yuxianji 伊斯蘭童子遇险记 Iceland Boys meeting Danger. Author: Ion Svensson. Translator: Hebeisheng Ganling Liu Baohua河北省甘陵刘保华 (Liu Baohua from Ganling in Hebei. Yanzhou 1931.

Bibliographie B

Holy Bible, New International Version (Anglicised edition), London: Hodder and Stoughton 1979, 1984, 2011.

P. Hermann Fischer SVD, Augustin Henninghaus, 53 Jahre Missionar und Missionsbischof, Steyler Missionsbuchhandlung 1946.

Hartwich, Richard (Hrsg.), Steyler Missionare in China Bd.1: Missionarische Erschließung Südshantungs 1879-1903, St. Augustin, Nettetal 1983-1991.

Henninghaus, Augustin, P. Joseph Freinademetz SVD. Sein Leben und Wirken. Zugleich Beiträge zur Geschichte der Mission Süd-Schantung, Yenchoufu 1920.

Huppertz, Josefine, Ein Beispiel katholischer Verlagsarbeit in China. Eine zeitgeschichtliche Studie, Studia Instituti Missiologici Societatis Verbi Divini, Nr. 54, Nettetal 1992.

Kang Zhijie 康志杰, “Tianzhujiao yinglian chuyi 天主教楹联刍议” (Catholic Couplets), Xueshu tansuo 学术探索Academic Exploration, May, 2012, pp. 84-88。

Knöpfler, Alois, “Die Akkomodation im altchristlichen Missionswesen”, Zeitschrift für Missionswissenschaft 1/1911, pp. 41-51.

Malek, Roman, Das Chai-chieh lu. Materialien zur Liturgie im Taoismus. Dissertation, Frankfurt a. M. u. a. 1985.

– “Christian Education and the Transfer of Ideals on a Local Level: Catholic Schoolbooks and Instructional Material from Shandong (1882-1950)”, in: 将根扎好 - 基督宗教在华教育的检讨,主编王成勉Setting the Roots Right – Christian Education in China and Taiwan, Wang Chengmian ed., Taipei 2007, S.79-155.

– “Bible at the Local Level. Notes on Biblical Material Published by the Divine Word Missionaries (S. V. D.) in Shandong (1882 – 1950)“, 40 pages, with 10 Plates. (第二届圣经与中国国际研讨会The Second International Workshop on the Bible and China , Jan. 5-8, 2002). Manuscript, will be published 2015.

R. Pieper, Unkraut, Knospen und Blüten aus dem „blumigen Reich der Mitte“, Steyl 1900.

Puhl, Stephan, Georg M. Stenz SVD (1869-1928). Chinamissionar im Kaiserreich der Republik. Missionspolitischer Kontext in Süd-Shandong am Vorabend der Boxer. Hrsg. P. Malek. Nettetal 1994.

Motsch, Monika, „Lin Shu und Franz Kuhn – zwei frühe Übersetzer“, Hefte für Ostasiatische Literatur 5/1986, pp.76 – 87.

– „Zwischen Indien und dem Westen. Neue Tendenzen chinesischer Übersetzungstheorie und Übersetzungspraxis“, Orientierungen, 1/1995, pp.1-12.

Qian Zhongshu 钱锺书, “Lin Shu de fanyi” 林纾的翻译 (The Translations of Lin Shu), in: Qian Zhongshuji钱锺书集: Qizhuiji 七缀集 (Works of Qian Zhongshu: Seven Essays), Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2001, pp. 89 – 133.

Qian Zhongshu, Guanzhuibian 管锥编 (With Pipe and Awl), in: Qian Zhongshuji钱锺书集, Beijing: Sanlian shudian 2001, 4 vols.

Rivinius, Karl Josef SVD, Die katholische Mission in Süd-Shantung, Sankt Augustin: Steyler Verlag 1979.

– Im Spannungsfeld von Mission und Politik: Johann Baptist Anzer (1851-1903), Bischof von Süd-Shandong, Nettetal 2010.

Stenz, Georg M., Reise-Erinnerungen eines Missionars. Meine Fahrt von Steyl (Holland) nach Shanghai (China) und ins Innere von China, Trier 1894.

– Ins Reich des Drachen, Ravensburg, Father Alber Verlag (ohne Datum).

– In der Heimat des Konfuzius. Skizzen, Bilder und Erlebnisse aus Schantung, Missionsdruckerei Steyl 1902. und Einl. von A. Conrady, Leipzig: R. Voigtländers Verlag 1907.

– Beiträge zur Volkskunde Süd-Schantungs, Hg und Einl. Von A. Conrady, Leipzig: R. Voigtländers Verlag 1907.

Jón Svensson, „Nonni und Manni in Seenot“, Neue Abenteuer auf Island mit Nonni und Manni, Freiburg im Breisgau 2008, pp. 82-127.

– „Abenteuer auf dem Meer“, Ein Priester erzählt von seiner Heimat: Nonni, Leipzig, 1981, pp. 157 – 173.

de Waal, Anton, Valeria oder der Triumphzug aus den Katakomben, 1884, 1885, 1896 (3rd ed.), pp. 382.

Zheng Zhenduo郑振铎, Zhongguo suwenxue shi 中国俗文学史(History of China’s Popular Literature), 2 vols, Shanghai shudian 上海书店1984.

Chinese Abstract

中文概要: 圣教小说山东鼓词

本文研讨二十世纪初山东圣言会出版的文学小故事,是马神父(Father Prof. Dr. Roman Malek) 在德国华裔学志图书馆收集的兖州印书局的一小部分。小故事的内容分成三部分,一,圣教古史小说山东鼓词,二,古代罗马致命故事,三,儿童文学。本文使用中西比较方法:“圣教古史小说鼓词”和“洪水灭世剧本”与圣经旧约有关原文对照。两个古罗马致命故事对照Wiseman, Fabiola 和de Waal,Valeria的原文小说。“ 伊斯兰童子遇险记”对照 Ion Svensson 写的小孩子的故事。在中国传教的神父常常被批评为小看中国文化的帝国主义者,这个指责不是没道理的。不过这些小故事证明,译者一般尽力探讨两个文化的共同点。这一方面是延续耶稣会在中国传教的政策,同时学习和适应中国传统文化。另一方面,也是继承一个中国古老传统:早在汉朝,“说文解字”已经定义,翻译家最基本的本事就是做媒。四世纪在中国传播佛教的僧人也是这个道理,还做了进一步的探讨:高僧道安重视忠实翻译而著名印度和尚鳩摩罗什注重传播文雅风格。后来中国僧人为了适应老百姓的口味发展出变文,俗讲。“做媒”也是山东天主教译者的方法。为了吸引老百姓,他们采用传统说书,说唱,如山东鼓词,山东戏剧的艺术形式和内容。特别是费金标翻译编写的山东鼓词,独特新颖,很有创造力。这里也应该佩服那时山东神父的勇气,敢出版这些小故事,把中国和欧洲拉在一起。

莫芝宜佳,博士,教授

汉学家,爱尔兰根和波恩大学。

[1] The full version of this article was published in Rooted in Hope: China – Religion – Christianity, Festschrift in Honor of Roman Malek S.V.D. on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday, ed. Barbara Hoster, Kirk Kuhlmann, Zbigniew Wesolowski S.V.D., Monumenta Serica Monograph Series LVIIII, 2 vols., Monumenta Serica Institute: Routledge New York 2017, vol.2, pp. 617-647

[2] Malek, “Christian Education and the Transfer of Ideals on a Local Level: Catholic Schoolbooks and Instructional Material from Shandong (1882-1950)”, in: 将根扎好 - 基督宗教在华教育的检讨,主编王成勉Setting the Roots Right – Christian Education in China and Taiwan, Wang Chengmian ed., Taipei 2007, S.79-155.

[3] “Illustration 12: Fei Jinbiao’s Shengjiao gushi xiaoshuo guci 圣教古史小说鼓词 (1918)”, in: Malek, “Christian Education”, p. 154.

[4] Barbara Hoster (Monumenta Serica, Editorial office, M.A.) first introduced me to this theme and helped me to find relevant material. My sincere thanks go to her and to the staff of “Monumenta Serica”.

[5] Yanzhou Catholic press of the S. V. D. (Yanzhoufu tianzhutang yinshuju huoban 兖州府天主堂印书局活版). Yanzhou兖州 is nowadays called Ji’ning济宁in Shandong Province. For the history and activities of the printing house see Huppertz, Katholische Verlagsarbeit in China.

[6] For all Bible references I have used the Holy Bible, New International Version (Anglicised edition)

[7] Father Joseph Hesser (transl.), Gujing lüeshuo古经略说, Yanzhou 1905. Father Hesser translated Ignaz Schuster’s (1838 – 1869) Biblische Geschichte des Alten und Neuen Testaments from German into Chinese. See Malek, “Christian Education”, p. 111. Malek, “The Bible at the Local Level”, Monumenta Serica 64 (2016) 1, pp. 137-172.

[8] Zheng Zhenduo郑振铎, Zhongguo suwenxue shi 中国俗文学史(History of China’s Popular Literature), vol. 2, chaps. 8, 13.

[9] Detailed list in Bibliography A. See Malek, “Christian Education”, pp. 112f, illustration 12. Malek, “Bible at the Local Level”, pp. 167-168, figs. 3 and 4. Huppertz, Katholische Verlagsarbeit in China, p. 53. Kang Zhijie 康志杰, “Tianzhujiao yinglian chuyi 天主教楹联刍议”, p. 86 (notes 7 and 8).

[10] All songs are printed in italics, prose passages in normal script. 提罢西江月,再把古传明 (No. 7 “Judith”, p. 60). 列位,你说。。。是谁?(No. 6, p. 7) 说书没有贰咀。得丢下文头。再说那头。(No. 8, p. 65). 好歇歇喘喘吸袋烟(no. 6, p. 94) 再拧拧琵琶继续红绒(no. 6, p. 114) 要说是见面怎么样/只得是下回续纶音 (no. 6, p. 16).

[11]凶荒年大兵围京城/城里的吃物贵百成/一驴头值钱八十吊/鸽子粪五吊钱一升/百姓们实在不能过/人吃人好夕顾生命(no. 6, p. 49)

[12]有的是供着夜叉鬼/红胡子绿眼睛红嘴唇/有的是供着恶模样/那青脸红发也当神/那猪嘴獠牙他也供/还有那兽蹄是鸟身/那人头鱼尾也都有/那牛头马面恶狠狠/数不尽多少斜神像(no. 6, p. 86).

[13]方面大耳精明过人。将来是个有大能为的材料. (no. 2, p. 7)

[14]读过了诗书念文章,真正是过目能成诵. (no. 2, p. 11)

[15]巴比隆王柏落大。百拜右达王厄则下陛下。侧闻我王威震人寰。德感地。夷狄归心。金乌顺命。晷影倒退十度。一日转长五时。此千古未闻之事也。且御体沉疴。立占勿药之喜。寡人不胜欣慰。爰肃贺函。并呈薄礼。乞笑纳。诸惟钧鉴。(no. 6, p. 96) jinwu金乌Golden Crow: In legend it is said that there is a three-legged golden-coloured crow in the sun, so in antiquity people called the sun “golden crow”. guiying晷影is an instrument which measures the times according to the shadow of the sun.

[16]好马还不背双鞍鞯/这好女怎么嫁二夫男?(No. 3, p. 95)

[17]此书系费金标,将古经灭世纪,按戏剧体裁,描情画景,读之令人心惊.

[18] 我乃天上天神。告明天主赏善罚恶。天主造了天地万物为人享用。命人在世修德立功。死后升天享福。当作天主义子。。。天主命俺。托给诺厄一梦。救他一家八口不死。。。天主要用洪水灭绝。真可惜呀。 (p. 2)

[19]唱:说此话我就要升天而去/白: 诺厄呀,诺厄,切莫要当梦中是些虚言。(p. 3)

[20] 木工唱:你要造船是一百六/价钱少了俺不行/生唱:铜钱给你一百整/阴天下雨一般同/出来一人劝着唱:官价原是一百二/两家公道不必争/生唱:是是是来随我去/拣选材料到山中 (p. 5)

[21]众人说:这个老头子越老越古怪。你还能灭这个世界不成. 唱:昨夜里三更天我偶作一个梦. 众人说:我知道你是做梦咧。唱:这一梦做的那真是不强. 众人说:不错。你做的梦不强是就啦. 唱:普世上下大雨洪水落地. 众人说:别管绿水红水。下的越大越好。如今天旱的很了。不下大雨还不行咧?(p. 5f)

[22]凶人唱:你试试这把刀快呀不快/举钢刀要劈开你的天门 (p. 8)

[23] 我的主正坐在五彩云霄/算一算灭世界日期到了 (p. 14)

[24] 天神唱:有天主罚世界显了全能/下大雨只下的普世皆平/只见那地上的人都淹死/上树的也如同水里滚龙/上山的爬岭的先也有命/到后来一个个水把命倾/这场雨只下了四十天整/四十天四十夜没有少停/不必论平地里水有多大/就让那高山上水也皆蒙/是蚂蚁要入地穴中有水/是飞禽有翅膀也难腾空/这一次灭世界作表记/到后来再有人也许惊醒 (p.14f)

[25]白:哈哈哈哈!天主呀。天主。真是可赞美的了!(p.16)

[26] Kang Zhijie mentions that in Southern China religious couplets were banned, if they did not conform strictly to the Catholic faith. (Kang Zhijie, “Tianzhujiao yinglian”, p. 86.

[27] Malek, “Bible at the Local Level”, p. 155.

[28] Malek, “Christian Education”, p. 108.

[29]乃枢机主教Wiseman所作著名小说,经费金标先生用鼓词体载译出,分两册共二四四页,定价一角五。Advertisement in Svensson, Icelandic Boys Meeting Danger. (See Bibliography A)

[30] Nicholas Patrick Wiseman, Fabiola. Or the Church of the Catacombs (1854), Reprint 2012.

[31]诗曰: 皇皇天主道理真/朝闻夕死孔子云/豁然贯通识正路/至死不变成好人no. 5, p. 23. Quote from Lunyu“Liren” 论语,里仁:朝闻道,夕死可矣。A still better quote in the martyr context would be Lunyu, “Weilinggong” 论语,卫灵公“杀身成仁。(To die for humanity).

[32] For attempts to interpret Confucian teachings and “filial piety” in the light of the Bible see Malek, “Bible at the Local Level”, p. 23.

[33] Wiseman, Fabiola, pp. 73ff.

[34](父亲唐桂林说)。。。来救俺那儿的活命。还有他娘的眼泪。我的苦口。费了多些功夫。俺那儿才说有了回心转意。叫你这一番吓诈。又把俺儿送到死地去了。叫俺儿舍了爹娘。成个不孝之子这算什么道理呢。况且人都劝他活。你偏劝他死。别说与理不合。也算大反人情了( no.5, p. 25)

[35](傅斐斯) …/你叫我升天没有路/你叫我入地没有门/你还要快快捻我走/你叫我哪里去存身。。。。别说我不走。连你也走不了。一面说着。一面用手把法小姐推倒床上了。(no. 5, p. 42)

[36] Wiseman, Fabiola, p. 212

[37]他坐在西京是狠心/生就的面貌凶恶样/说起来真是吓死人/果然是身高一丈二/

列位,您说真这么高么。我说这是论的中国尺子。要说西国是论米达。您到那里量量才算准。这不过是说他身量很大就是了。杠要少抬。慢慢的往下听罢。

那膀宽三尺零三分/

这又是抬杠。敢说。 人家都说膀宽三尺。你怎么说三尺零三分呢。叫我说呀。人有瘦的时候。也有胖的时候呢。光胖这三分么。说书唱戏。不兴抬杠的。慢慢往下听罢。

那猪嘴獠牙不像人/明煌煌一对钢铃眼/…. (no. 5, p. 44)

[38] The slip reads: “Khu min da jung. Erzählung aus dem 4. Jht. v. R. D. A. de Waal, übersetzt v. P. Roeser.”

[39] Valeria, p. IX (Foreword to the third edition), p. 44, p. 46 (note 5)

[40]不久,瓦肋利亚神目见了天堂上的圣人圣女。其中也有他的母亲。请他同他父亲升天。到底有个深渊隔着。也有个大龙张口伸舌要吞他们。瓦肋利亚如同梦里说话一样叫他父亲都听见。忽然他说。大大你别害怕。使脚跐大龙的头。赖耶稣的圣名他不能害你。咱们快快的过去罢。我的母亲等候我们。苦是暂苦。福是总福。(p. 32). Valeria, p.143f.

[41] For Catholic western schools see Rivinius,Johann Baptist Anzer, chap.15, pp. 725-761.

[42] Puhl, Georg M. Stenz SVD, p. 85 – 128.

[43] Stenz, Reise-Erinnerungen eines Missionars. Ins Reich des Drachen. In der Heimat des Konfuzius. Beiträge zur Volkskunde Süd-Schantungs.

[44]众位教友。 你想想。天主能舍了有信德的孝子么。有一晚上。天主发现给西地盎(儿子)。他做了南柯一梦。梦见奥神父。笑嘻嘻的。站在床前手拿苦像。对他说。西地盎你能效法耶稣表样。背你世俗的十字架。天主爱怜你。允了你的祈求。你来罢。我给你领洗。叫你将来升天国。享无穷的福乐。西地盎喜出望外。乐不可言。。。西地盎醒了。才知是南柯一梦。(Filial Son, p. 40f.)

[45] In two of them P. Stenz was involved personally. In 1897, the Steyler missionaries P. Henle and P. Nies while spending the night in Stenz’s house, were killed by the Chinese Society “Broad Swords” (Dadaohui 大刀会). Afterwards, the German Government used this as a pretext to occupy Jiaozhou peninsula and make it a German colony. (Rivinius, Johann Baptist Anzer, pp. 487-627). 1898 in another such incident, P. Stenz himself was captured and tortured for three days. Though this had been caused by the wrongdoing of some Christian converts, there followed a punitive expedition of the German army, which P. Stenz accompanied, in the course of which two Chinese villages were completely demolished. (Rivinius, Johann Baptist Anzer, pp. 589-615).

[46] 此篇小说,系用白话著作,粗俚不文,最易明悉,令人阅读,难以释手,智者蒙诲,愚者启迪,开其心,明其目,确系古今奇观,世所罕有。Preface by Liu Baohua 刘保华, from Ganling, province Hebei (Hebei sheng, Ganling河北省甘陵), dated Dec. 15, 1929. Catholic Church in the district Xian (tianzhutang Xianxian天主堂 献县)。

[47] His grave is in the Jesuit cemetery in Cologne where there is a “Nonni Fountain” showing a young boy reading a book.

[48] Jón Svensson, Neue Abenteuer auf Island, pp. 82-127. Jón Svensson, Ein Priester erzählt von seiner Heimat: Nonni, pp. 157-173.

[49] (船长)向我笑了一笑,两手扶在我头上,低廉嘟噜的说了一套,我们虽然不懂,大估量他说的不错,因为许多次我们听见他重说“可怜的孩子(Poor little boy)“. (p. 135)

[50]到如今连司铎的品位也没有得到,大如今数十岁了,再想上外教人地方传教去,也就晚一点了。(no. 9, p. 153)

[51] Malek, “Christian Education”, pp. 99-101. For the history of “accommodation” see Knöpfler, “Die Akkomodation im altchristlichen Missionswesen” pp. 41-51.

[52] „说文解字“卷六“口”部第二十六字:“囮“译也。… 率鸟者系生鸟以来之,名曰“囮“…. “南唐以来,小学家都申说”翻译“就是”传四夷及鸟兽之语“,好比”鸟媒“对”禽鸟“的引诱 …. Qian Zhongshu, “Lin Shu de fanyi”, p. 89. Motsch, “Lin Shu und Franz Kuhn”, p. 78f.

[53] “Goethe, „Maximen und Reflexionen”: “Übersetzer sind als geschäftige Kuppler anzusehen, die uns eine halbverschleierte Schöne als höchst liebenswürdig anpreisen: sie erregen eine unwiderstehliche Neigung nach dem Original”.

[54]“五失本”之一曰:“梵语尽倒,而使从秦” .“失本“之二曰:梵经尚质,秦人好文,传可众心,非文不合” . Quoted from Qian Zhongshu, Guanzhuibian vol. 4, p. 84 (全晋文卷158: “翻译术开宗明义”). For the three school of Chinese translation see Motsch, “Zwischen Indien und dem Westen”, pp. 2 – 5.

[55]但改梵文为秦,失其藻蔚虽得大意,疏隔文体,有似嚼饭与人,非徒失味,乃令呕穗也。Quoted from Qian Zhongshu, Guanzhuibian vol. 4, p. 85 (全晋文卷158).

[56] Drum Songs of the Old Testament, Vol. 1 (Genesis), Fei Jinbiao’s Preface.

[57] Wiseman, Fabiola, pp. 135 – 138. Fei Jinbiao, Short Drum Songs about Martyrs, p. 35.

[58] Rivinius, Anzer, pp. 395-400 (“Missionaries seeing themselves”). Stenz wrote: The blood of martyrs had to flow everywhere, in order to fructify the teachings of christendom. (Ins Reich des Drachen, p. 250). In the same vein the Steyler General Superior P. Janssen: “And would it not be a great blessing, if one had the fortune to become a martyr?”(Henninghaus, P. Jos. Freinademetz, p. 137).